Q&A with UC Davis expert Marc E. Lenaerts

(SACRAMENTO, Calif.) – Migraine headaches can strike any time and be debilitating, making it impossible to work or enjoy even life’s simple pleasures. They affect approximately 12 percent of the population living in the U.S. and are three times more prevalent in women than men. The neurology team at UC Davis provides excellent care and outcomes for migraine sufferers. In this Q&A Marc Lenaerts, director of outpatient neurology and a headache medicine specialist, discusses the condition and how to manage it.

What is migraine?

Migraine is a condition or syndrome – not just a headache. Headache is a key symptom but not always present during a migraine. Someone with fewer than 15 headache days per month has episodic migraine while those who experience 15 or more headache days per month have chronic migraine. Migraine headache can be moderate or severe, with throbbing pain, unevenly distributed between each side of the head, made worse with physical activity. The pain is caused by nerve-controlled inflammation of the dura, or the membrane between the brain and the skull.

Are there other symptoms associated with migraine?

Symptoms can include cravings or loss of appetite, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, sweating or cold extremities, lightheadedness, water retention (swelling) and head congestion. Patients can also experience cognitive changes, such as difficulty putting sentences together or feeling confused. Sensitivity to environmental stimuli such as lights, noises, smells, movements, heat or cold, is typical. Emotional symptoms are common, too, such as irritability or depression. Conversely, some feel elated, as if they’ve had a surge of energy. Some migraine sufferers experience auras, seeing bright shimmers, zig-zag lines or other geometric shapes, such as a checkerboard. They may experience blank or blurred vision, or see their surroundings in one color such as yellow or pink. In more complex cases, visual hallucinations can occur. Auras can include tingling or numbness on one side of the body, usually hand and face, weakness, language and/or speech impairment, loss of balance, vertigo and even loss of consciousness.

How is migraine syndrome diagnosed?

The International Classification of Headache Disorders has specific criteria for migraine – at least five headache attacks with known symptoms and no underlying cause. There is also a category of migraine attacks without head pain. There is no biological marker for migraine, such as a genetic test or imaging tool. Ultimately, diagnosis is up to the provider.

What distinguishes migraine from other kinds of headache?

Because migraine can involve pain in the cheeks or areas near the sinuses, it can be confused with a “sinus headache,” which is not an official diagnosis but a symptom of sinusitis or acute sinus infection.

A so-called “tension headache” is characterized by non-descript head pain with mild, diffuse, pressure-type pain without other symptoms. It rarely impairs patients. Cluster headache is rare, primarily affecting men and characterized by attacks of dreadful pain usually around one eye. Symptoms include sweating, teary eyes, drooped eyelid, congested and/or dripping nose. The attacks occur at particular times (spring and fall, early morning) in clusters.

What causes migraines?

The trigeminal nerve likely initiates inflammation of the dura, transmitting and controlling pain and limiting local blood flow. Calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) is a key chemical in this system, which is called the trigemino-vascular system. CGRP is released by the trigeminal nerve, which plays a major role in migraine headache pain. There may also be genetic causes of migraine. There are multiple triggers that, individually or collectively, precipitate a migraine attack. Common examples include estrogen level drop (pre-menstruation), alcohol use, stress, cold weather fronts and sleep deprivation.

Does every migraine have a trigger?

Most migraines are trigger-less or we mischaracterize triggers. For example, before a migraine, a patient may crave chocolate and experience a headache after eating it. The migraine is not actually “triggered” by the chocolate; rather the patient’s craving for chocolate can be a precursor symptom of the migraine episode.

Are some people more at-risk for the condition?

Women are three times more likely to have migraine syndrome than men and more likely to develop chronic migraines. Migraines are more common in the Western Hemisphere, probably for genetic reasons. Hormones play a role in migraines; for example, a woman’s menstrual cycle and the onset of menopause can increase risk. Women also are at higher risk for chronic migraine and stroke in their young adult years.

How is migraine treated?

Acetaminophen and opiates block the pain message sent to the brain. Non-steroid anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) such as Ibuprofen or Naproxen can block inflammation in the body. Triptans (Sumatriptan) target the specific inflammation of the dura to help with pain, gastrointestinal issues and related symptoms of sensitivity to environmental stimuli. Overuse of these medications, however, can lead to rebound headaches, now called medication overuse headache. These are defined as worsening of an existing headache with use of relief medication more than two days a week.

The American and international headache societies recommend preventive treatment when headaches occur weekly or more. Medications that treat hypertension, epilepsy or depression/anxiety can help prevent migraine when taken daily. They can take up to three months to take effect, so they’re not a quick fix. An anesthetic nerve block to cranial nerves above the eyebrow, upper neck and in the nose also can help. Non-pharmacologic approaches can prevent migraines, too. Procedures called biofeedback relaxation and cognitive behavioral therapy, which we provide here, can also help.

Until very recently, Botulinum toxin was the only FDA-approved medication for chronic migraine, injected into the skin of the patient’s temples, forehead, occipital area, upper neck and shoulders every three months. Studies show that people with chronic migraine experience approximately nine fewer headache days per month for three months after the injections.

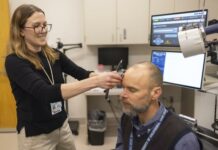

The FDA has approved a new medication called Erenumab that demonstrated preventive efficacy for both episodic and chronic migraine. Erenumab targets and blocks the GCRP receptor, which significantly contributes to pain signals during a migraine. Erenumab is a once-monthly self-injection with very limited side effects. Devices that stimulate the cranial nerves via a small electric current on the forehead or even magnetic current on the back of the head have shown benefit. A few stimulators are even implanted in the head. With miniaturization and technological advancement, we can expect flourishing options in this treatment category in the near future.

Does lifestyle play a role in migraine prevention?

Maintaining a healthy lifestyle, including eating an all-natural diet, regular exercise and a healthy weight is important, and regular sleep is paramount. Stress relief techniques such as yoga, Pilates and meditation can also be preventative.

Is migraine syndrome life-long?

Migraine is a lifelong condition but symptoms occur most commonly between teenage years and about 60. Some patients’ migraine days will fade as they age; however some will continue to experience migraines well into their 80s.

What would you like to see in migraine research?

I would like to see more insight into the role of the placebo effect in migraine, headache and pain in general. Also further research into the effect of self-management and lifestyle modification is paramount, as it should be in medical care overall.

UC Davis Health. (2018, June 27). Oh, my aching head! The who, what, why and how to cope with migraine [Press release]. Retrieved from http://www.ucdmc.ucdavis.edu/publish/news/contenthub/12999

(21+ years strong)

Welcome to the brighter side!

Get in front of local customers! 24/7 (365)