Named Conservationist of the Year by the John Muir Association

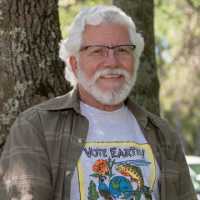

Rocklin, CA,- In a ceremony this spring at John Muir’s former house and orchards, now a National Historic Site, the John Muir Association named Sierra College Professor Emeritus Joe Medeiros, Conservationist of the Year.

For 40 years, this award has gone to those who are dedicated to carry on Muir’s legacy of protecting the environment. The honor went to Medeiros for his 35 years as an educator and for his efforts and passion to protect the Sierra Nevada Mountains, not to mention, said one colleague, for his sense of humor and his story telling.

Medeiros secured his master’s degree from CSU Fresno in 1974 and took a full-time position at Modesto Jr. College. He taught biology and botany during spring and fall semesters while each summer, for the next nine years, he worked as a ranger in the High Sierra southeast of Yosemite at the Devils Postpile National Monument.

Named for a cliff of dark basalt columns extruded 100,000 years ago from volcanic fissures, the postpiles look from below like squared off rock posts welded together, rising as high as sixty feet. At the top, visitors walk on a natural patio where, long ago, glaciers sheared off and polished the solid mass of volcanic rock.

Medeiros brought his two daughters with him to Postpile. “They ran wild there,” he said. “Barefoot, with snacks and drinks in their backpacks and safety whistles worn as necklaces.” They lived in the Ranger’s quarters, canvas wall tents on wooden platforms. “We cooked meals on a wood stove, and sat by campfires at night,” he recalled. “It was heaven.”

Some 60 years before, around 1910, engineers had planned to blast to pieces the postpiles and use the rubble to build a dam in the San Joaquin River. Before this geologic wonder was demolished, John Muir and collaborators persuaded the federal government to stop the dam project. President William Taft signed the executive order in 1911 that protected the postpiles, along with 800 acres of wildland, and the 100-foot high Rainbow Falls, creating the national monument that later became the summer playground of the Medeiros daughters.

The young professor Medeiros saw the history of the piles, an area close to his heart, as a perfect example of the potential environmental damage likely to come from California’s accelerating development, and of the need to protect our natural world.

He saw John Muir, who saved the postpiles from destruction, as a visionary and thinker who was also pragmatic. “He carefully selected his words but did not shy away from confrontation when he saw egregious acts against nature—those he sought to reduce or derail.” These included the felling of giant sequoias, which had lived 2,000 years, the wholesale demolition of the magnificent Sierra forests and the damming of Tuolumne River to flood Hetch Hetchy, Yosemite National Park’s twin valley.

Among Muir’s greatest contributions, said Medeiros, were launching the preservation and conservation movements that caused the National Park system to be established; and his eloquent writings that inspire nature lovers to this day. “He encouraged people who are tired and weary of the relentless business of life to go outside and take a saunter,” he said, “preferably somewhere wild, the wilder the better.”

Medeiros found, on his own, the books and writings of Muir and read them during high school and early college. “It was the late 1960s and evolution wasn’t even in the science curriculum,” he said, “and the field of ecology was just emerging.” It was Rachel Carson’s blockbuster Silent Spring that awakened Medeiros and other students at the time. “A stable and resilient Earth threatened by toxins and biocides. This was serious and we had to do something.” He paused, adding, “Muir would have loved Rachel Carson.”

Authors like Aldo Leopold, Paul Ehrlich and Raymond Dasmann also deeply influenced Medeiros, a voracious reader. Today, as editor in chief of the Sierra Press, he is producing books to inspire a new generation. As the only publisher in the country affiliated with a community college, the Press is known for such titles as King Sequoia: The Tree That Inspired a Nation, California Glaciers, and Tahoe Beneath the Surface.

During his 16-year tenure at Modesto College, among many other initiatives, Medeiros organized staff members and students to participate in conservation events and projects like restoring wetlands in California’s Central Valley. He was the principal organizer of the popular Great Valley Museum of Natural History. As he would throughout his career, he sought to foster appreciation of and concern for nature.

In 1990, Medeiros came to teach botany, ecology, and environmental studies at Sierra College, comprised of three primary campuses in northern California: one at Rocklin in the Sierra’s foothills, another in Grass Valley in mid-elevation forests, and the third at Truckee near the Donner Summit.

As a mentor and educator, Medeiros has organized hundreds of field trips leading several thousand students over the years into nearby mountains and forests. Through annual and wildly popular Earth Day celebrations, with lectures at high schools and colleges, and in talks to community groups, he has reached thousands of people. For several years, he has been talking about climate change—from the perspective of the oldest known tree species on Earth, the Great Basin Bristlecone Pine.

Medeiros has stood beside and taken students to see these ancient trees, one specimen verified to be 5,067 years old. The bristlecone groves are at 10,000 to 12,000 feet in the White Mountains on the east slope of the Sierra, southeast of Yosemite near the Nevada border. A collection of living and dead specimens provides a 10,000-year record of Earth’s climate.

Over the centuries, bristlecones have suffered major climate shifts, migrating up or down the slopes to accommodate changing temperatures and precipitation. “As the cause of the current warming cycle,” he said, “I wonder whether it will be us modern humans who deal the death knell to the bristlecone, so resilient to other natural fluctuations and catastrophes.”

“Dinosaurs flourished on Earth for 150 million years, while modern humans have been here for only 50 to 60 thousand years,” said Medeiros. He says we can find no evidence that humans will be here even ten thousand years from now.

“The hand of what Muir called ‘Lord Man’ is heavier than ever before,” he said. “How a species could be eliminated in such a short time through our ignorance and arrogance gives me pause, and saddens me deeply.”

Recently, Medeiros has been talking with younger folks, starting with his three grandchildren. He speaks to their elementary school classes, leads trips for youngsters at nature preserves like those of the Placer Land Trust, and hands out nature guides to teachers and parents. Medeiros believes that our youth will find a way to protect what they love and “there’s plenty to love about wildness and nature.”

(21+ years strong)

Welcome to the brighter side!

Get in front of local customers! 24/7 (365)